The “Silly” Solution

A couple of nights ago, in the Esolangs Discord server, a user named kepe was trying to solve last years’ Canadian Computing Competition (CCC for short) problems. He couldn’t solve some of them, and most importantly he didn’t know graphs well and the next CCC was the next day. So a thread has been made made to help him. After some time, a “troll” joined the thread (She didn’t want me to use her name. She was probably not serious, but that’s how I’ll refer to her from now on). The first question of CCC 2022 quickly grab her attention, because she had already solved a variant of it before.

Here’s the question itself;

Finn loves Fours and Fives. In fact, he loves them so much that he wants to know the number of ways a number can be formed by using a sum of fours and fives, where the order of the fours and fives does not matter. If Finn wants to form the number 14, there is one way to do this which is 14 = 4 + 5 + 5. As another example, if Finn wants to form the number 20, this can be done two ways, which are 20 = 4 + 4 + 4 + 4 + 4 and 20 = 5 + 5 + 5 + 5. As a final example, Finn can form the number 40 in three ways: 40 = 4 + 4 + 4 + 4 + 4 + 4 + 4 + 4 + 4 + 4, 40 = 4 + 4 + 4 + 4 + 4 + 5 + 5 + 5 + 5, and 40 = 5 + 5 + 5 + 5 + 5 + 5 + 5 + 5. Your task is to help Finn determine the number of ways that a number can be written as a sum of fours and fives.

First, let’s look at kepe’s code:

pub fn fours_fives(n: u32) -> u32 {

// n = 4a + 5b

// find how many combinations of (a, b) are valid

// for any given a, there won't be solutions (a, X) and (a, Y)

// so we just need to find X

let mut total = 0;

for a in 0..(n / 4) {

// n = 4a + 5b

// b = (n - 4a) / 5

let q = n - 4*a;

if q % 5 == 0 {

total += 1;

}

}

total

}

The code is well documented, and easy to understand, it produces wrong answers for n values that divide 4,

but that is not a big issue.

Now let’s look at her co- Oh wait, she also didn’t allow me to use her code :(, luckily ChatGPT gives a similar solution to hers, so we’ll use that:

int countWays(int n) {

if (n < 0) {

return 0;

}

// Create an array to store the number of ways for each value from 0 to n

int dp[n + 1];

// Initialize the array to 0 using memset

memset(dp, 0, sizeof(dp));

// Base case

dp[0] = 1;

// Fill in the array using the recursive relation

for (int i = 4; i <= n; ++i) {

dp[i] += dp[i - 4];

}

for (int i = 5; i <= n; ++i) {

dp[i] += dp[i - 5];

}

return dp[n];

}

If it is first time seeing this code, it might not make too much sense to you. It uses something called dynamic programming which is a short form of saying “recursion bad loop good”. I had an entirely different idea, but after seeing dynamic programming solution I thought mine was silly, so I called it “The Silly Solution”. The idea was pretty simple, my goal was to find the amount of 5’s in the solution that had the most amount of 5’s, let’s call that number \(n\), since I can replace 4 fives with 5 fours, then there’d be \(\lfloor \frac{n}{4} \rfloor\) more solutions. It made sense, and here’s the deobfuscated code below:

int number_of_solutions(int n)

{

int n5 = n / 5;

int d = n - n5*5;

n5 -= (-d) % 4;

return n5 / 4 + 1;

}

But I couldn’t check whether the above code was correct or not because the first version of her code

had some bugs. And I missed one of them, so the results produced were unreliable. So about 30 mins later

I posted an obfuscated version of the code to the server. And the troll informed me that the for n=16

the C version of the code returned 2 and the python version of the code returned 1. She then later explained

that it was caused by the modulus operator behavior in C. It turns out that C standard allows some modulus

operations to yield negative results. So replacing (-d)%4 with (4-d)%4 fixed most of the issues. However,

the code still produced wrong results for some values. But it was easy to fix, I just needed to check whether

n5 was less than zero or not, and return zero if it was. With those little changes, the first fully functioning

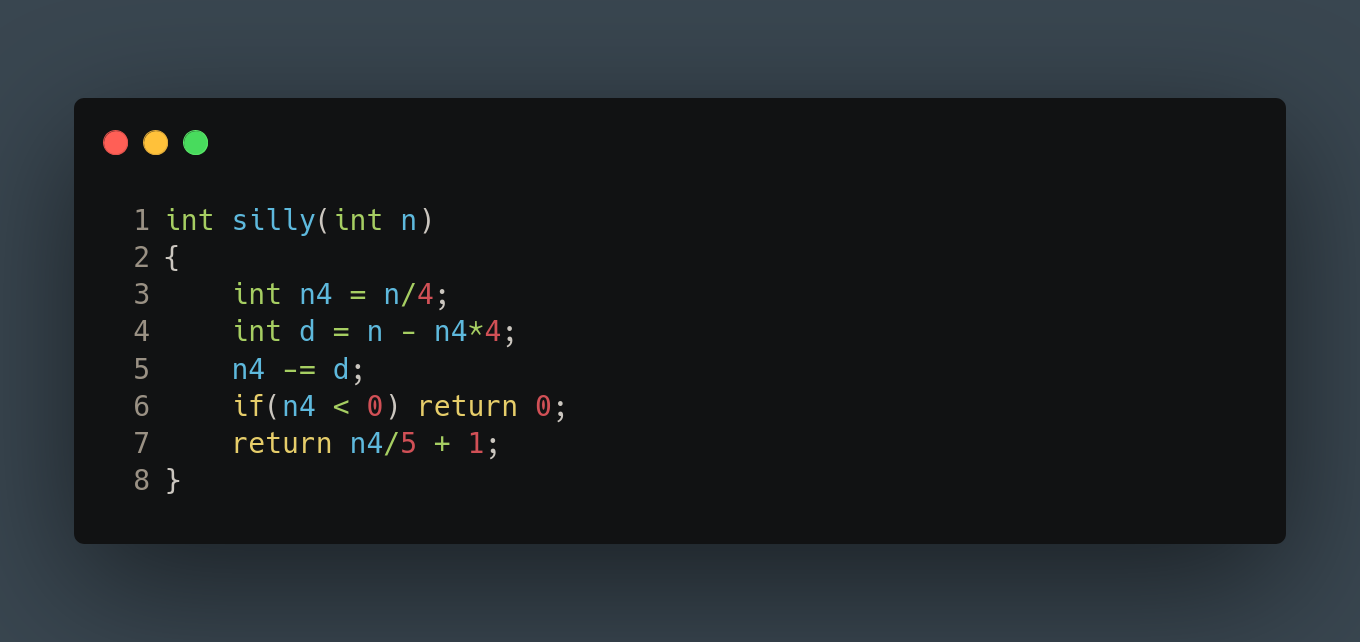

version of the “silly” was ready. (Oh and I also rewrote it, it now finds the number of fours in the solution with

the most amount of fours):

int silly(int n)

{

int n4 = n / 4;

int d = n - n4 * 4;

n4 -= d;

if(n4 < 0) return 0;

return n4 / 5 + 1;

}

And here’s a stripped down version:

int silly2(int n)

{

return (n/4) - (n/5) + (n % 5 == 0);

}

Before we get into the next section, I want to explain how exactly it finds the number of fours. First, it divides n

by 4 and sets it equal to n4. But this is not enough, because not every number is divisible by 4 (duh). So it also calculates n % 4, and

sets it equal to d (I avoided using modulus operator and went with n-n4*4 there because it is faster, yes I am obsessed

with tiny and probably negligible speed improvements). Since this value can take values 0, 1, 2 and 3; I manually counted how many fours I had to remove

in order for the difference to be divisible by 5:

- For

d=0, I don’t have to remove any fours since it is already divisible by 5. - For

d=1, I have to remove 1 four, - For

d=2, I have to remove 2 fours, - And similarly for

d=3, I have to remove 3 fours.

Oh wow, what a coincidence! The number of fours I have to remove is exactly equals to d! The algorithm then returns 0 if

the number of fours end up being negative, and returns n4/5 + 1 otherwise. But I haven’t stopped there, I wanted to generalize it as much as possible.

Wear your seatbelts people, we are going to the number theory realm!

First Generalization: Why Not Any Two Favorite Numbers?

Before we begin, I’d like to explain the notation that I’ll be using in the following text. The greatest common denominator of two numbers \(a \text{ and } b\), will be denoted with \((a, b)\). Similarly, the least common multiple of two numbers \(a \text{ and } b\) will be denoted with \([a, b]\).

With that out of the way, we can begin. Let’s add an entirely different person into the question: Jane. Jane is an unusual girl, her favorite two numbers always change. Let’s call them \(p \text{ and } q\). Jane is also not great at math, she wants us to determine the number of ways to form any given number as a sum of her favorite numbers \(p \text{ and } q\).

Now let’s prove to her if \(g = (p, q)\), then we can only form numbers that are divisible by \(g\), and also show that if a number \(r\) is divisible by \(g\). The question of forming it using \(p\) and \(q\) is equivalent to forming \(\frac{r}{g}\) with \(\frac{p}{g}\) and \(\frac{q}{g}\). First claim is trivially easy to prove, let a formulation \(r\) to be \(px + qy\) where \(x \text{ and } y\) are integers, since \(g \mid p\) and \(g \mid q\), the formulation itself is also divisible by \(g\). And if we let \(p = g\alpha\) and \(q = g\beta\) where \((\alpha, \beta)=1\). This gives us \(r = px + qy = g(\alpha x + \beta y)\) and \(\frac{r}{g}=\alpha x + \beta y = \frac{p}{g}x+\frac{q}{g}y\). This proves our second claim.

We can calculate the GCD of two numbers using the Extended Euclidean Algorithm, but whilst calculating the GCD, I also want to calculate the \(x \text{ and } y\) that forms \(g\), as they will come in handy in the future. I won’t delve into how algorithm works and why it works here, because it’d occupy a lot of space. Instead, I’ll leave it as an exercise to you, the reader. Here’s a C++ code that performs the Euclidean Algorithm:

struct EuclideanAlgorithmResult

{

int gcd = 0;

int x = 0;

int y = 0;

};

constexpr std::pair<int, int> divmod(int a, int b)

{

int d = a / b;

return {d, a - d*b};

}

constexpr EuclideanAlgorithmResult euclidean(int p, int q)

{

EuclideanAlgorithmResult result;

int max = std::max(p, q);

int max_copy = max;

int min = p + q - max;

if(min == 0) return {max, (max==p), (max==q)};

int f_0 = 1, f_1 = 0, f_2 = max;

int s_0 = 0, s_1 = 1, s_2 = min;

while(true)

{

auto[q, m] = divmod(max, min);

if(m == 0) break;

f_0 = std::exchange(s_0, f_0 - q * s_0);

f_1 = std::exchange(s_1, f_1 - q * s_1);

f_2 = std::exchange(s_2, f_2 - q * s_2);

max = min;

min = m;

}

result.gcd = min;

result.x = (max_copy == p ? s_0 : s_1);

result.y = s_0 + s_1 - result.x;

return result;

}

Now, let’s focus on the actual question, let the Jane’s smallest favorite number to be \(p\), the other one to be \(q\) and our target number to be \(r\). By intuition, we can see that we can replace \(\frac{[p, q]}{p}\) amount of \(p\)’s with \(\frac{[p, q]}{q}\) amount of \(q\)’s. We’ve shown earlier that solving this problem for \(p, q, r\), where \((p, q) \neq 1\) is equivalent to solving it for \(\frac{p}{(p, q)}, \frac{q}{(p, q)}, \frac{r}{(p, q)}\). So we can safely assume that \((p, q)=1\). This also makes our past claim a bit clearer since \([p, q] = pq\) if \((p, q)=1\). Let me rephrase it to make things clear, “We can replace \(q\) amount of \(p\)’s with \(p\) amount of \(q\)’s”. So our goal should be to find the amount of \(p\)’s used in the formulation that has the most amount of \(p\)’s. Then similarly, we’ll divide this value by \(q\) and add one to get the total amount of formulations. Let’s start writing our code:

constexpr int jane(int n, int p, int q)

{

if(q < p)

{

std::swap(p, q);

}

EuclideanAlgorithmResult result = euclidean(p, q);

if(n % result.gcd != 0)

{

return 0;

}

n /= result.gcd;

p /= result.gcd;

q /= result.gcd;

auto[np, d] = divmod(n, p);

np -= /*???*/;

if(np < 0)

{

return 0;

}

return np / q + 1;

}

Oops, we immediately came across another problem. What should we subtract from np? If you recall, for the \(p=4\) and \(q=5\) case that number turned out to be

equal to d itself. But we are not that lucky here so let’s think about it more.

Let’s say that removing \(t\) amount of \(p\)’s gets us a number that is divisible by \(q\). So the congruence \(pt+d \equiv 0 \pmod{q}\) has to be satisfied. If we subtract \(d\) from both sides, we get this congruence: \(pt \equiv -d \pmod{q}\). Now I want you to imagine a number \(\bar{p}\) such that \(p\bar{p} \equiv 1 \pmod{q}\). If we multiply both sides of the congruence by \(\bar{p}\) we can find \(t\) in terms of \(d\) and \(\bar{p}\): \(t \equiv -d\bar{p} \pmod{q}\). But what is the value of \(\bar{p}\)? And most importantly, does such a number exist? Let’s investigate.

\(p\bar{p} \equiv 1 \pmod{q}\) implies that there exist an integer \(z\) such that, \(p\bar{p} + qz = 1\). But wait, since 1 is the GCD of \(p\) and \(q\), the Euclidean algorithm has already given us the value of \(\bar{p}\) and \(z\) as \(x\) and \(y\), respectively. Consequently, we found the value of \(t\) as \(t=-dx \mod{q}\). To avoid C++’s negative modulus results, I’ll also add the product \(pq\) before performing the modulus operation. As it contains \(q\) as a factor, it won’t change the result.

constexpr int jane(int n, int p, int q)

{

if(q < p)

{

std::swap(p, q);

}

EuclideanAlgorithmResult result = euclidean(p, q);

if(n % result.gcd != 0)

{

return 0;

}

n /= result.gcd;

p /= result.gcd;

q /= result.gcd;

auto[np, d] = divmod(n, p);

np -= (p * q - d * result.x) % q;

if(np < 0)

{

return 0;

}

return np / q + 1;

}

Second Generalization: Multiple Favorite Numbers

This is where I just propose a boring solution and finish this post… Seriously, I’ve tried many methods, but I couldn’t come up with a solution that will lower the time complexity below \(O(n^{k}\log(\min(f_{k+1}, f_{k+2})))\) for \(k+2\) favorite numbers, \(f_{k+1} and f_{k+2}\) being \(k+1\)st and \(k+2\)nd favorite numbers, respectively. Given that this was supposed to be a fun little problem it costed me a lot of time. I’ll just give you a C++ code that will do the work and leave this problem behind. Anyways, the strategy is for a given set of favorite numbers is simple, and it probably came to mind for some of you. Given \(k\) favorite numbers and a target number \(n\), we’ll pick one favorite number \(f\) and recursively check for target numbers \(n, n-f, n-2f, \dots\) with the remaining \(k-1\) favorite numbers.

constexpr int multiple(int n, int f1)

{

return (f1>0)*(n%f1==0)*(n/f1);

}

constexpr int multiple(int n, int f1, int f2)

{

return jane(n, f1, f2);

}

template<typename T>

concept Int=std::is_same_v<T, int>;

template<Int... Nums>

constexpr int multiple(int n, int f1, Nums... nums)

{

if(n == 0) return 1;

int total = 0;

for(int i=n; i >= 0; i-=f1)

{

total += multiple(i, nums...);

}

return total;

}

Here’s the code itself. If this problem has interested you, feel free to work on it and share your own results with everybody. Who knows, maybe there are more efficient ways to solve this problem. But that’s it for me, see you in the future!

Update: After posting this post, the problem caught attention of a user named Moja. And he posted a simple solution which I completely overlooked.

def count_parts(favs, n):

curr = [1] + [0]*n

for fav in favs:

for i in range(fav, n+1):

curr[i]+=curr[i-fav]

return curr[-1]

Which is another case of utilizing the dynamic programming technique. It has a time complexity of \(O(nk)\) for \(k\) favorite numbers. At the end of the day dynamic programming won, but it was still a fun problem to work on, who knows, maybe there is a clever solution that lowers the time complexity even more.