Bedwars & Math

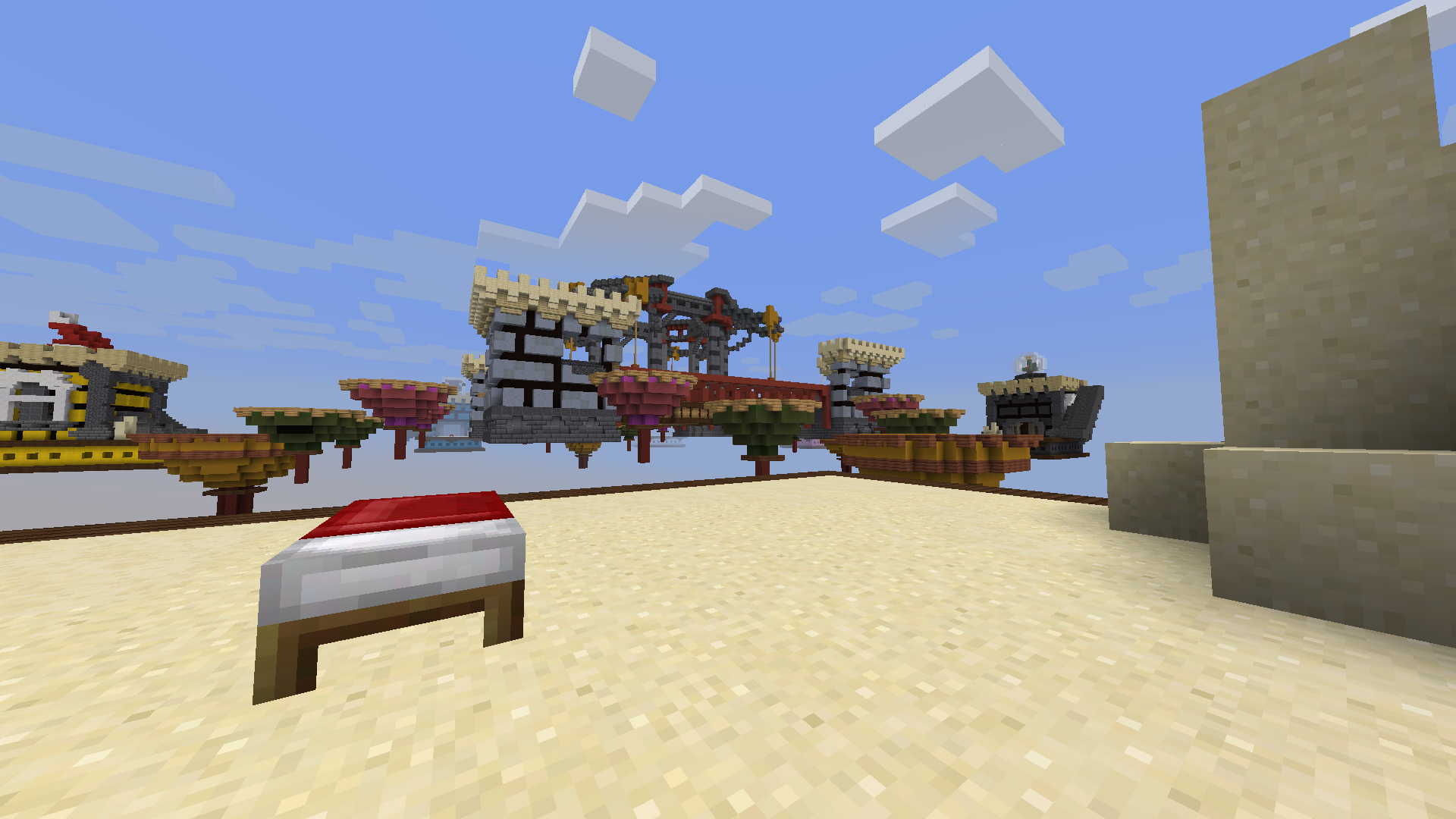

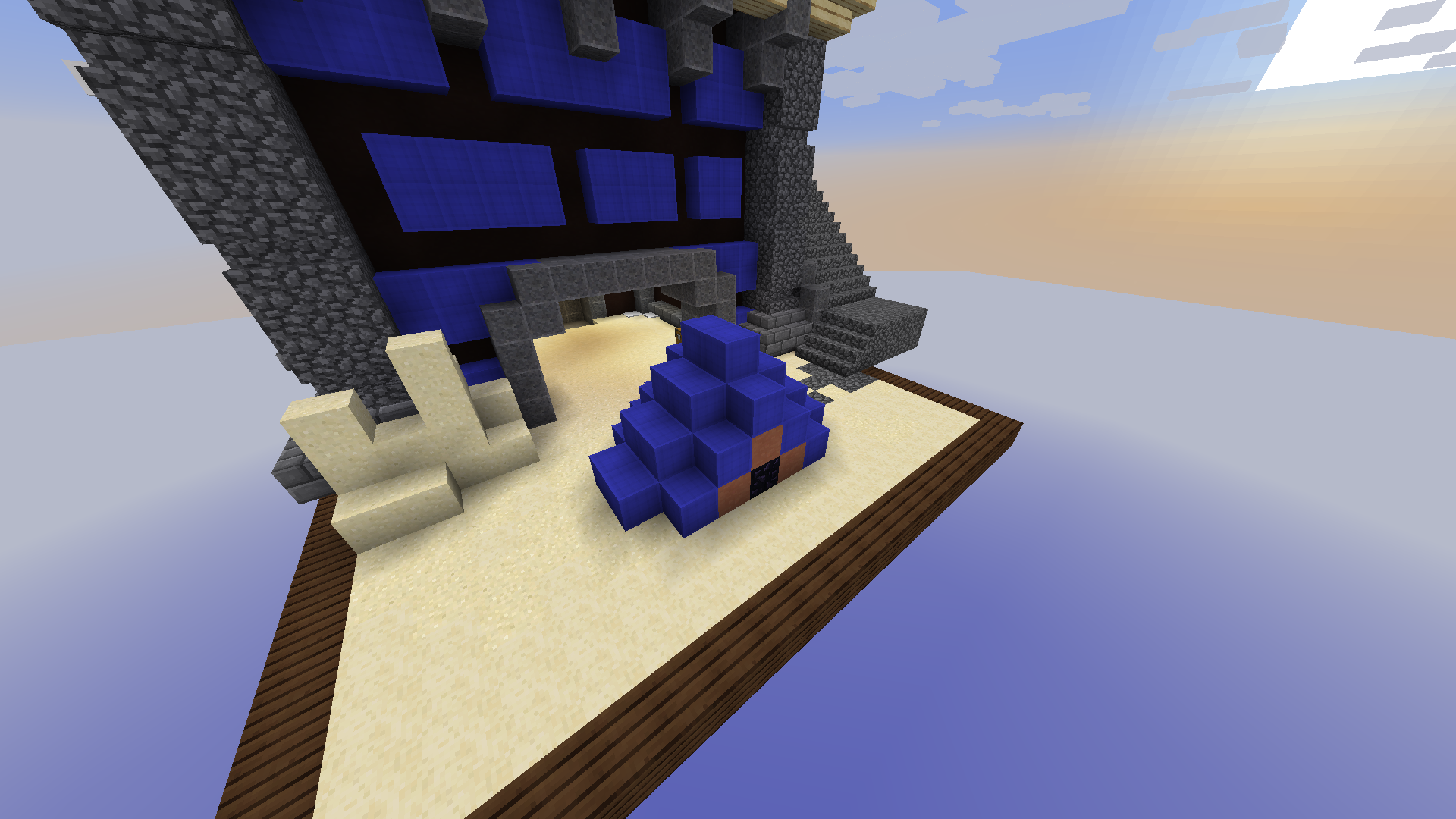

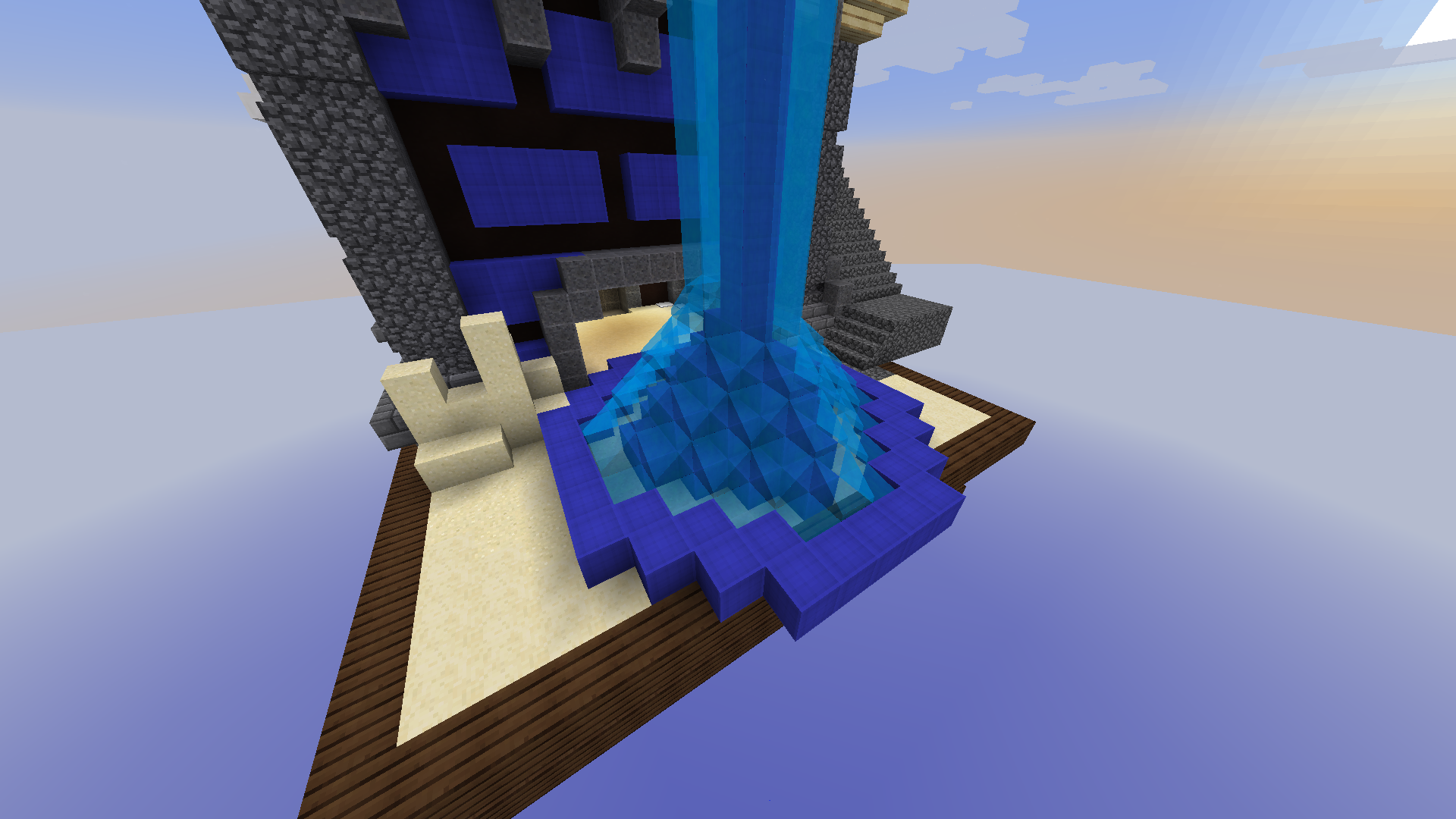

In 2021, I was playing a lot of bedwars games with a friend of mine. We played rather well together and when we got bored with playing competitively, we started trolling other bedwars players. We’ve done a lot of trolls, but one of them was building obscure bed defenses. For example the defense below is called “The Éclair Defense” and it contains obsidian in its first layer, glass (or clay for some servers) in its second layer and wool for its last layer. It is pretty effective for servers that use clay as the explosion resistant block. It also has another variant named “Éclair with water” where we build up to the height limit and place a water bucket down and build a little barrier around the defense to prevent water from spilling everywhere.

Another obscure defense idea that came to our minds and what made this post a reality was a simple one: Three layers of obsidian. But we’ve run into a problem immediately, as we didn’t know how many blocks we needed, we didn’t know how many emeralds it was going to cost us. Of course one of us could boot up a creative world and count the amount of blocks needed after the game but what if we wanted to build bigger defenses? What we’d do then? So instead, after the game I wanted to find a formula for how many blocks needed for a given layer. Let \(B_{n}\) to be the blocks needed for \(n^{th}\) layer. I knew some values of \(B_{n}\): \(B_{1}=8\) and \(B_{2}=18\). I could’ve tried to see a pattern by manually counting some layers, but I’ve chosen to not do that, just because I wasn’t expecting an easy to see formula. But anyways, I started to observe defenses to find a relation between consecutive layers. And the key observation I made was, to build the next layer, you have to copy the current layer one block up and then build the bottom part of the layer. Check the GIF below.

So we have this recurrence relation

$$B_{n+1}=B_{n}+b_{n+1}$$

where \(b_{n}\) denotes the amount of blocks needed at the bottom on the \(n^{th}\) layer. Similarly, by observation we can deduce a relation between \(b_{n+1}\) and \(b_{n}\).

They have a similar relation, but this time it does not depend on anything else.

$$b_{n+1}=b_{n}+4; \hspace{0.4 cm} b_{1}=6$$

Here’s a GIF if you want to see that relation yourself.

There are a lot of method as to solve these kinds of equations, you can directly solve this non-homogenous recurrence relation, or you can also use generating functions, but for the sake

of simplicity I won’t delve into those. Let’s write down every single equation from \(n=1\) to \(n=k\) for some fixed number \(k\).

$$ b_{1}=6 \hspace{1.1cm} \\

b_{2}=b_{1}+4 \\

b_{3}=b_{2}+4 \\

\vdots \\

b_{k}=b_{k-1}+4$$

Now if you add these \(k\) equations side by side, what you’ll notice is that the terms \(b_{1}, b_{2}, \dots b_{k-1}\) are on the both sides of the final equation, so you can cancel those out and get; $$b_{k}=6+\sum_{i=1}^{k-1}4=6+4(k-1)=4k+2$$ And upon replacing \(k\) with \(n\), we have a formula for \(b_{n}\). Now we’ll apply the same process to \(B_{n}\), we’ll write down the equations from \(n=1\) to \(n=k\) for some fixed \(k\), and add them all. $$ B_{1}=8 \hspace{1.4cm} \\ B_{2}=B_{1}+b_{2} \\ B_{3}=B_{2}+b_{3} \\ \vdots \\ B_{k}=B_{k-1}+b_{k} $$

Upon adding these equations and cancelling the necessary terms, we get; $$B_{k}=8+\sum_{i=2}^{k}(4i+2)=8+4\sum_{i=2}^{k}i + \sum_{i=2}^{k}2=8+4\left(\frac{k(k+1)}{2}-1\right)+2(k-1)$$ $$B_{k}=2k^{2}+4k+2=2\left(k+1\right)^{2}$$

So we found the formula we wanted. Though, I’ll use the notation \(Bw(x)\) instead of \(B_{x}\), simply because I like it more. We can stop there, but I’ll continue just a bit more to derive a couple of more equations. If you recall what I was aiming for, I originaly needed a formula that counts how many total blocks I need to build \(x\) layers. Let’s call it \(Bws(x)\) and find a formula for it as well.

$$Bws(x)=\sum_{i=1}^{x}Bw(i)=\sum_{i=1}^{x}2(i+1)^{2}=2\sum_{i=2}^{x+1}i^{2}=2\left(\frac{(x+1)(x+2)(2x+3)}{6} - 1\right)=\frac{2x^{3}+9x^{2}+13x}{3}$$

You can also define the inverse of \(Bw(x)\) for \(x \geq 0\) and denote it as \(Bwi(x)\); $$Bwi(x)=\sqrt{\frac{x}{2}}-1$$

And lastly, you can apply the same process to a very similar minigame, Eggwars. I won’t derive them here, I’ll leave it as an exercise to you. But below, you can find the formulas for the layer function, its inverse and the sum function, respectively.

$$ Ew(x) = x^{2}+\left(x+1\right)^{2} $$ $$ Ewi(x) = \frac{\sqrt{2x-1} - 1}{2},\hspace{0.3cm} x\geq0$$ $$ Ews(x) = \frac{2x^{3}+6x^{2}+7x}{3}$$